Chapter seven

Photo: Hilda Gertrude Hasch Belchamber aged three, with her baby sister Lilian, 18 months - 1895. Hilda has an air of melancholy about her even at this age.

Young Hilda Gertrude was six years old when her grandmother Eliza committed suicide and nine when her maternal grandfather, Isaac died. Her paternal grandfather, Claus Hasch had died at the age of fifty-seven on July 3, 1886 before she was born and her paternal grandmother, Elizabeth would live for another sixteen years, dying August, 16 1916, at the age of seventy-seven, when Hilda was twenty two. At the ages of six and nine, she was certainly old enough to mourn the passing of her mother’s parents, if indeed she had seen anything of Eliza in the years that she and Isaac had been separated.

Who knows what impact it had on her mother but Sarah has come down through the generations as a woman who was a force with which to be reckoned and who gave her timid eldest daughter, more than one black eye long after she had married John Henry. One wonders what ‘Jack’ did about such attacks.

Or Johann for that matter. Probably nothing! Johann, or John as he was called, looks a placid sort from his photograph. He was born on February 13, 1862, in the small town of Lobethal in the Adelaide Hills. His parents were Claus Hasch, born 1829, Barmstedt, a plasterer/builder from Schleswig-Holstein, duchies which belonged to Denmark and Germany at different times, and Elizabeth Johanna Sophia Catharina Kohlhagen, from Mecklenburg, Germany.

Elizabeth was the daughter of Johann Heinrich William Kohlhagen and Elisabeth Sophie Schoenfeldt and was born on June 17, 1839 in Wokrent. I do not know the exact reasons as to why Johannn and Elisabeth decided to set sail for the Great South land but life in Mecklenburg could be harsh and remained so until the revolution of 1918. No doubt they left for the same reasons that hundreds of thousands of others left in the 19th century. There was absolute rule under the two Mecklenburgian duchies, even to such practices as applying for permission to marry to emigrate. No doubt my great-great-great grandparents had to apply and were grateful it was granted from the day they set foot in Australia.

The land they left behind had been a dark place for a long time. With the annulment of serfdom in 1820 many landowners stopped caring for the poor and finding either work or housing became nearly impossible. The power of the trade guilds made it difficult for people to set themselves up in business and provide for themselves and so, in the early 19th century began a mass emigration which would include my ancestors. In all, several million people emigrated from Germany in this period to the new nations of Australia, Canada and the United States in the main.

Records show that many were reluctant to leave their homeland but they had no choice. To survive they had to leave. Some 261,000 Mecklenburgers left their home country between 1820 and 1890 for other lands. No wonder that Johann and Elisabeth were among them and were prepared to sail to what was ‘the ends of the earth’ to Europeans, to give their children a better life. As they did.

Photo: Johann (John) Henry Nicholaus Hasch c. 1882.

Johann’s parents Johann Heinrich and Catharina Maria (Randt) were still alive when the family set sail for Australia. Johann senior, born in 1775 in Grob Belitz, Mecklenburg died in 1849, at the age of seventy-four, in Wokrent, three years after his son and family had arrived in Adelaide and Catharina, born in 1779 in Nuekirchen, Germany, died two years later, in 1851 at the age of seventy-two.

Johann would not have known of his parents deaths until some months later … or perhaps even longer given the vagaries of mail delivery in the 19th century.

Johann was a carpenter, as in fact was my father, and he and his family arrived in South Australia on the ‘George Washington,’ on Saturday, January 24, 1846. Johann was forty-two and Elisabeth thirty-five. My great-great-grandmother, Elisabeth, was six years old. Her sister Catharina was fourteen; Anna twelve; Dorothea four and Johann was a baby.Photo: The Port of Hamburg in 1850. The Kohlhagen’s and Hasch families both set sail for South Australia from here.

Johann took his family to settle in the small German community of Lobethal in the Adelaide Hills. The fact that he did so suggests it is possible he was fleeing religious persecution for this village had been established by the Lutheran pastor, August Ludwig Christian Kavel as a place of refuge for his ‘flock’ just five years earlier. The Kohlhagens may not have come from exactly the same villages, but they certainly came from the same area. Given how people followed familial, cultural and religious connections when they emigrated – all very understandable – I don’t think there is much doubt that the Kohlhagen’s and perhaps Claus Hasch, had links with Pastor Kavel and his flock.

Lobethal is thirty-three kilometres from the city of Adelaide which was a reasonable distance at the time. To travel so far instead of settling in Adelaide itself, suggests that the Kohlhagen’s had a motivation to do so and that would have been the expectation of help and support when they arrived.

This community had its beginnings in 1838 when George Fife Angas went to London as a director of the South Australian Company to try and promote colonisation. While he was there he met Pastor August Ludwig Christian Kavel who was trying to organise for Lutherans (who were being persecuted by the King of Prussia, Friedrich Wilhelm III) to emigrate. Angas was moved by the plight of the Lutherans and not only persuaded Kavel that South Australia was a suitable place for emigration but also financially assisted them with a generous £8,000.

PHOTO: Johann Wilhelm Koelhagen and his wife Elizabeth (Schoenfeldt).

The first German settlers in South Australia arrived on November 25, 1838 at Port Adelaide which was still, unfortunately known by its original name of Port Misery. Surveyed by Colonel Light some years earlier, the site was swampy and a long day’s walk from the settlement of Adelaide. While Port Misery officially became Port Adelaide on May 23, 1837 it took time for those arriving in the new colony to see it in a more positive light.

The Germans who began to arrive in 1841 went on to establish villages at Klemzig and Glen Osmond, now suburbs of Adelaide and Lobethal and Hahndorf. The latter holds the title as Australia’s first German settlement and is still a popular tourist destination in the Adelaide Hills. It is also where we have a small farm which we bought in 1997 without my knowing how close the links were between area and ancestors.

In 1880 the Reverend I. Ey wrote: ‘The bulk of the persecuted Lutherans of Lobethal, with their beloved pastor, G.D. Fritsche, came out in the ship, Skjold, after an eighteen week trip, during which no fewer than forty-four deaths occurred. This must have been a ghastly voyage and when compared to the three deaths on board the ship which Eliza’s former employer, Dr John Grace, had charge of as surgeon, shows what a difference there can be in death rates on such a voyage. They were temporarily taken care of and welcomed by the somewhat earlier pioneers of Klemzig and Hahndorf, and some went up to the Tanunda district.’

Johann’s brother Christian, who emigrated with him, would move to the Tanunda area which is a part of the Barossa Valley and his descendants remain there to this day. Lobethal's story begins in Prussia (now Germany, bordering Poland). From 1807 on, the emperor, Kaiser Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia, tried to unify his church, the Reformed (Calvinist) church, with the Protestant Lutherans in his country. The minority Lutherans refused as the Kaiser had named himself as Bishop of his new Union Church, effectively making himself its head. For Lutherans, separation of church and state was (and is) a fundamental doctrine, and the more they refused the more punitive the Kaiser became. The very name Lutheran was banned; pastor's property was confiscated and congregations were fined. By the 1830s Lutherans were being jailed for their faith; even deputations sent to speak with the Kaiser were imprisoned.

There is a sense, tracing my German ancestors, that they were an argumentative lot at worst and strongly opinionated at best. The latter trait has made its way down the family line without a doubt.

There were many other reasons why Mecklenburgers were looking to emigrate so it is not surprising that these persecuted Lutherans looked to do the same. Getting an exit visa was not easy and often Prussians had to agree to emigrate with their pastor as a whole congregation. Pastors Kavel and Fritsche embarked on their plan with this in mind.

By 1840, Fritsche's health was failing and he applied for permission to take his congregation to Australia, where he felt God wanted him to be. Pastor Fritsche and his congregation sold up, pooled their resources, and were finally granted an exit visa while they waited at the port of Hamburg. However, they were £300 short. British Quakers helped them with loans, as did Fritsche's fiancée's mother, Frau Nerlich, enabling them to charter a ship. However, that ship needed repairs and delayed the near-penniless group in Hamburg for weeks. A substitute vessel, Skjold, set sail on July 3, 1841.

Kavel’s vision was that all of the Lutherans from the various villages of Klemzig, Glen Osmond and Hahndorf would settle together. He looked at buying land in the Barossa Valley but those who had arrived earlier were settled and content and not everyone shared the same doctrinal views as Pastor Kavel. Tschicherzig, Klemzig and Kay, from where Pastor Kavel’s flock came, were small villages in Prussia, which no longer exists but which was, at the time an independent German state. All of the villages are now a part of Poland owing to border changes following the end of World War Two. In early 1842 the Pastor and eighteen families at Hahndorf decided to go it alone. One of the group, Ferdinand Muller, had been working as a shepherd for the South Australian Company and he told them of a beautiful valley he had seen to the north, near the western branch of the Onkaparinga River, where there was land for sale.

Once again Frau Nerlich came to the rescue and loaned money. As she was now Fritzsche’s mother-in-law this is not surprising. The group purchased 168 acres at one pound an acre. The same land today is worth many thousands of dollars an acre and no doubt the families which remained found themselves relatively wealthy landowners in the future. Mine had however long gone by the end of the 19th century.

But it was not as simple as it seemed because land could only be held by naturalised British citizens. This may well be why Johann Kohlhagen became naturalised within years of arriving in the colony, as did his son-in-law Claus Hasch. A tailor named Krumnow came to the rescue of the Lutherans and took possession of the land on their behalf. Something of a religious fanatic with communist leanings, he solved one problem while creating many more and it took the Lobethal Germans eight years to get their property for themselves.

Photo: Lobethal in the 1870’s.

On May 4, 1842 Pastor Fritsche read from the Bible and named their new home. The community drew lots to apportion the new land. The democratic Hufendorf layout of Lobethal's house blocks was traditionally German; long, narrow strips of about three acres. The house was built at the end, by the road, and the creek ran across the blocks, accessible to all. Behind the houses were farm buildings such as cellars with lofts, then vegetable gardens and orchards and some of the animals were tethered by the creek. Oats, barley and rye grew at the far end. Other stock was pastured in nearby forest and fields. The main street was originally where Mill Road is now and many cottages along there are from the earliest days of the settlement.

Crude one-room slab huts were replaced in time by larger two-room cottages, barns, cellars, bake ovens and smoke-houses, most built in the German style. A high degree of craftsmanship can still be seen in the remaining buildings, some built entirely without nails. Roofs were thatched, and later covered with wooden shingles. Several shingled roofs are still visible under galvanized iron roofs today.

The traditional Prussian farmhouse was built with a cooking passage or flurkuchenhaus (black kitchen) and this is how the Lobethal houses were built. These large, vented or brick domed cooking halls would usually face the front door. The centrally located wood-fired oven and chimney would heat the entire house. While winter in the Adelaide Hills is never as cold as Europe it can get below minus zero overnight and the sensibly built and heated Lobethal homes were probably far cosier than anything built by the British colonists. The Germans also built smokehouses on the rear of their homes to cure meat and fish.

Photo: The Lutheran Schoolhouse in Lobethal, 1850, where my great-grandfather Johann Hasch and his siblings went to school.

In 1843 work began on a permanent church building. Bricks fired in a kiln nearby were carried by women in bags and aprons on their way to Sunday worship. During the week, after work, the men of the town would work on the church. Finished and dedicated in 1845, Zum Weinberg Christi, or St John's, was the first permanent Lutheran Church built in Australia.

But all was not sweetness and light in the new community. In the year that Johann arrived with his family there was a major doctrinal dispute within the Lutheran community and a second church, St. Paul’s established. Lobethal has the oldest Lutheran Church in Australia and work began on building the church in 1843. It was dedicated in 1847 and is still in use today.

Photo: The Lutheran Church manse in Lobethal built 1847.

Despite risking their lives to move to the other side of the world in order to be able to practise their religion without the interference of the State, the Germans were an interfering and argumentative lot themselves. In 1863 a third church was established called Zum Kreuze Christi and in 1876 a fourth church, Zum Kripplein Christi. In the 20th century these churches were all amalgamated as one but when Johann Kohlhagen and his family arrived and when Claus married Elizabeth, it is clear there was less agreement and more dissent.

Perhaps one of the reasons why Claus and Elizabeth ultimately moved to Adelaide was because of the disagreements and dissent which were rife in the Lobethal community. Or perhaps it was because some time in the 1860’s Johann Wilhelm and his wife Elizabeth and their sons moved to Victoria to work the land. Johann died at Green Lake on May 13, 1881 and Elizabeth returned to live in Adelaide where her daughters had settled. She moved in with Elizabeth and Claus and was no doubt of great support to her daughter when Claus died five years later. Elizabeth lived until the age of eighty-seven, dying at her daughter’s home in 1893.

I am just grateful that all of my ancestors on both sides dropped their Lutheran, Catholic, Protestant and Jewish affiliations and enabled me to grow up without the constraints of religion. Australia is the most secular of all the developed nations and there is a lot to be said for it when one trawls through the religious dissent of the past.

But, despite doctrinal arguments the Lutheran settlers established a productive and substantial agricultural community which continues to this day. Dairy and beef farming and orchards thrived then as they do now. The South Australian Almanac for 1844 recorded statistics for the Lobethal settlers as: 50 acres wheat, 10 acres barley, 1 acre maize, 10 acres potatoes, 17 acres gardens, 40 cattle, 2 ponies, 32 pigs and 11 goats.

But it was not enough to grow crops - they had to be sold. Fruit, wheat, vines, corn, potatoes, hops needed a market and provisions which could not be home-grown had to be purchased. Adelaide was the only place that could happen. When Johann and his family settled in the Adelaide Hills there were no roads as we know them and no public transport. Usually the men would work the fields and the women would walk the fifteen miles across the hills with the produce on their backs. They made them tough in those days and none more so than the German women.

But the community thrived from the very beginning and before long apart from farmers there were carpenters, cabinet makers, brick-makers, gunsmiths, bootmakers, tailors, locksmiths, organ builders, clock makers, four millers, saw millers and of course stone-masons. And there was local beer by the time Claus arrived. In 1851 F.W. Kleinschmidt built a brewery near where the Mill chimney stands today. This building later housed the start of what was the famous Onkaparinga Mill at Lobethal, which produced some of the world’s finest woollen cloth for more than one hundred years. The mill closed in 1993 and is now a museum/craft/ art complex. My brother, Vince, had an exhibition of his photographic work there a few years ago – again with no knowledge of how close the family connection had been to Lobethal.

Eventually there would be two flour mills, two fruit and vegetable drying mills, two hop kilns and a cricket bat factory. There was also a small amount of gold mining in the Onkaparinga Valley from the late 1840’s and one wonders if Claus and his children went out on Sundays, after church of course, to see if they could find a few grains of gold to supplement the family income.

And life in Lobethal would be very like life had been in Germany, as the writer Friedrich Gerstacker wrote when he visited South Australia in 1851, some twelve years after the first Germans had arrived:

About an hour later, as I saw everywhere to the left and right of me small friendly houses, I came upon a farm, which I just had to have a look at. From the outside, you see, it looked exactly like one of our small German farms, with barns, stables, sheds etc, and to begin with I stood for a few minutes quite surprised. It was as if I wasn't in Australia, as if some guardian angel had whisked me back to Germany at the speed of thought, and now... but the blessed gumtrees...I was in fact in Australia!

In the yard a boy was harnessing the horses. That was a German harness and a German wagon, I could have sworn to it; and a maid came out of the barn with a typical German pitch fork in her hand. I just had to enter the house too. I jumped the fence, walked across the yard, opened the front door – the door handle was definitely not made in Australia, and I wouldn’t be surprised if my dear and amazing countrymen had brought the whole front door with them from Germany – and I knocked.

"Come in!" I stood in the middle of the room, and here, dear reader, if you want a really clear idea of what I saw, you must stop for a second and go into the first farmhouse you get to in Germany – the small quiet room which I entered was exactly like that in appearance and smell. Well, not quite so quiet, because a white-haired, red-cheeked and extremely grubby little boy sitting on his grandmother's knee at the fireplace was crying for all he was worth. The old grandmother herself was a true and outstanding example of an old German farmer's wife such as you would find only in the heart of Germany itself, and I am convinced that everything, right down to the brooches and shoe-laces, was genuinely German and that no English or Australian piece of clothing had ever touched her body.

But not only that: the oven, the chairs, tables, plates decorated with proverbs, the bowls with verses from the hymn book, the big chests with green roses and yellow forget-me-nots on them - in a word, everything was German and if you had taken a genuine farmhouse room, roots and all, from somewhere in Saxony or Prussia, carefully packed it in cotton-wool and transported it here, it could not have had a more genuine character about it than what I saw here.

(Friedrich Gerstäcker. Reisen um die Welt, Volume 4, 1853)

The biggest difference of course was that in Australia, despite the German appearance of their lives, the settlers had a freedom to live, of which those ‘back home’ could only dream. These Germans had sailed across the world in the hope of a new life and true freedom in this fledgling nation perched on the edge of Antarctica, and they had found all that they hoped for and more. The Germanness would disappear within a generation with language, clothing, homes and habits dissolving into a new and evolving form of Australianness.

The enduring things would be some foods and German-style dishes and some of the quaint houses and cottages which can still be found in Lobethal, Hahndorf and other small settlements in the Adelaide Hills. I have nothing of my German or Danish ancestry which has been handed down, except a few photographs and some family stories. The assimilation of settlers in early Australia was complete for most by the second generation. They anglicised their names, became naturalised and devoted themselves to the new country with dedication and passion. In many ways Germans were suited to Australia and Australia was suited to them. It was a ‘natural fit’ as it was with the English settlers and no doubt the reason why assimilation was so fast and so complete.

Whatever they had left behind it was not enough, as it was for many immigrants, to hold their hearts or even their culture. Having said that, no doubt they would be pleased to see South Australians in particular so ready to celebrate their German heritage and to acknowledge the gifts that these settlers brought. And no more so than in the wine industry, particularly in the Barossa and Clare Valleys but also in the Adelaide Hills. South Australia produces most of the country’s wine and some of the world’s best. Johann Gramp planted the first vines in the Barossa Valley in 1847 and they are still producing wine.

The world’s oldest grapevines are in the Hunter Valley, New South Wales and date from around 1830, but South Australia, Victoria and Western Australia are not far behind. Australia escaped the devastating Phylloxera outbreak, the grape root louse, which wiped out European vineyards and so still has vines which can be linked to the mid to late 1700’s. And many of them, thanks to our German settlers.

Claus Hasch the Third, had been born in Barmstedt, Schleswig-Holstein on April 1, 1829. Given the time-difference between Europe and Australia, my brother Wayne, would share a birthday with him 119 years later although while the first of April in Barmstedt it was the second of April in Adelaide. He arrived in South Australia nine years after his wife-to-be and her family had done so. Twenty-six year old Claus set sail on the La Rochelle, arriving at Port Adelaide on September 3, 1855. He claimed Danish nationality throughout his life but became an Australian citizen in September of 1865.

His arrival and his naturalization were in the same month that I was born. His family could trace their Schleswig-Holstein ancestry back for many years. His father, Dierich (Dierck) had been born in Kattendorf, Germany on October 16, 1782 but his mother, Anna Catherina Cathor, had been born in Barmstedt, Schleswig-Holstein. Dierich had moved to his wife’s town and he died at the age of seventy, on April 29, 1853, in Barmstedt. Anna outlived him by twenty-two years, dying on November 15, 1875 in her home-town. We do not have a birth date for Anna so she may well have been a lot younger than her husband.

Dierick’s father, Claus Hasch I, had been born around 1740 in Schleswig-Holstein and he died around 1800 in Kattendorf, Germany. His eldest son became Claus Hasch II. From the look of it, Claus Hasch I moved to Kattendorf when he married his German wife, Anna Schmuk. Kattendorf and Barmstedt are twenty-one kilometres apart and given the ‘back and forth nature’ of Schleswig-Holstein, in terms of whether it was Danish or German, the choice of ‘nationality’ was probably optional to some degree. My great-great-grandfather Claus, remained adamant he was Danish which makes me think that the family lineage as Danes went back a very long way.

Schleswig-Holstein had been Jutland originally and a part of Denmark but in the 19th century as the German Confederation grew in power, it made claims to the area. A war was fought in 1848 and a treaty signed in 1850 and both sides held claim to their rights. But the arguments continued and in 1855, the year Claus left for Australia, the arguments were growing more dangerous. In 1863 there was another war and by 1888 the only language being taught in Schleswig-Holstein was German.

Claus however was far away and could not have been greatly bothered because he had married a German woman, as had his grandfather, and had a family of young children who would call themselves Australian, as he now did.

He and Elizabeth married on July 22, 1861 in St. Paul’s Church, Lobethal. Whether Claus went to Lobethal on arrival to work and married and settled there or whether he met Elizabeth elsewhere and settled in Lobethal so she could be close to her family, I do not know. My great-grandfather, Johann Nicholaus was born on February 13, 1862 … just seven months after the marriage and was, I am sure, the reason for the marriage. He was not to become Claus IV, and in fact, none of Claus’s four sons would carry on the name.

Elizabeth, like so many women of the times, would have her nine children roughly two years apart. After her first-born, a son, there would be five daughters and then more sons. Anna Dorothea was born at Lobethal on May 21, 1864; Emma Friedericke Auguste arrived on May 17, 1866; Meta Friedericke on September 8, 1868; Ida Caroline on July 8, 1870; Pauline Wilhelmine on January 17, 1873; Hermann Dietrich on October 8, 1875; Henry on April 3, 1877 and Albert Wilhelm on May 26, 1880.

Henry and Albert were both born in Adelaide with Albert’s place of birth listed as Rose Park. Given that Claus will die at Rose Park in 1866 it looks like the family may have moved from Lobethal to Adelaide sometime in 1876. Perhaps the farm was not enough to support his large and growing family and Claus decided to go back to work as a stone-mason in the booming city of Adelaide, some 33 kilometres to the South.

Claus Hasch is mentioned in old newspaper reports as also running dairy cattle at his home in Rose Park, which had been declared a nuisance by neighbours for wandering into their gardens and damaging them. Claus died on July 3, 1886 at his Rose Park home. He was fifty-seven years old. His children ranged in age from twenty-four to six. No doubt with five daughters ranging in age from twenty-two to thirteen, Elizabeth had plenty of help at home with the three boys aged eleven, nine and six.

As the oldest male the task of supporting the family would have fallen to Johann. He may well have been working for his father and learning the trade since the age of twelve and perhaps eleven year old Hermann, became his apprentice when their father died. Given that Elizabeth remained in the Rose Park home, it is safe to assume that when Claus died she not only owned her home but had enough support to remain in it and raise her children. That was not always the case for women who were widowed in the 19th century.

There is no doubt that Claus was a skilled builder, as was his son. The homes which they built remain standing and in this day and age, as colonial blue and brownstones, are now valuable properties. Johann (John) built two houses in Castle Street, Parkside, Number 18 where my grandparents, Hilda and John lived and Number 20 where he lived with his wife, Sarah. The style of the houses is the same as the one his father Claus had built in Rose Park, at 8 Watson Avenue.

Photo: A house in Watson Avenue in 2011, built in the same style and at the same time as Claus Hasch built his home.

The house at 18 Castle Street must have been like a palace for ‘Jack’ Belchamber who had grown up in grinding poverty in the East End of London. He remembered going hungry and barefoot to school, with dripping on bread a staple… when there was food to be had.

The Belchambers had a long history of poverty, at times, terrible poverty. ‘Jack’s’ father, Alfred was the fifth of six children born to Henry, a boilermaker and Sarah Ann Williams). Henry, married Sarah Ann, a servant, aged 22, on August 28, 1853 at St. Leonard’s Parish Church, Shoreditch. They both made their marks, which suggests they were illiterate, and they are recorded as living at 17 Maria Street. Henry put his father’s profession as grocer and Sarah Ann put her father’s as baker.

Henry was recorded in the 1841 census as living with his parents and siblings in Kent but by 1851, the year his father died, he had moved to London, where he met and married Sarah. Henry was the son of James Belchamber, born about 1788 in Deptford, Kent and his wife, Elizabeth Bond, born about 1785 in Gosport, Hampshire. They were married by banns in St. Mary’s Parish Church in Lewisham, Kent on September 27, 1812. The newly-weds moved into accommodation in Effingham Place, which, was pulled down ten years later due to open sewage and rat infestation.

Photo: the brewery Lobethal circa. 1840.

If tracing my mother’s family ancestry reveals anything, it is poverty and suffering. The sad thing is that while this is not my life, it was hers from the time that she married. Certainly nothing like the poverty of her ancestors but poverty for 20th century Australia. Did that make her stronger? She was certainly resilient as her ancestors had to be.

James was a labourer and a japanner, or tin-plate worker, in the victualling yard within Deptford Dockyard. The yard was a place where provisions for the Navy were stored such as salt-beef, biscuits, beer, rum, chocolate, soap and tobacco. Little did he know his great-great-grandson, Max Belchamber, my mother’s brother, would become a merchant sailor during World War Two. James and Elizabeth later lived at 11 Fairey’s Buildings, Deptford, where he died aged 63 on November 2, 1851.

Elizabeth went to live with her daughter, Mary Ann Palmer at 6 Kerbey Street, Bromley, London after James’s death. She died just three years later on March 12, 1854, of bronchitis. The lungs represent grief and after the death of her husband, perhaps Elizabeth had no will to live. It is perhaps a sign that she loved him.

Deptford was home to Britain’s most important naval victualling yard until 1961. It was also where Peter the Great, the only Tzar to leave Russia, spent time learning ship-building.

Henry and Sarah had six children. Sarah Ann Eliza was born April 6, 1854, less than nine months after their marriage and perhaps the reason for it. She was born at 5 Mary Terrace, Bromley. Henry William was born October 10, 1856 at 5 New Street, Limehouse. Eliza was born October 24, 1858 at 28 Cottage Street, Poplar. Emma was born February 13, 1861 at 1 Caroline Place, Deptford, Kent. Whether both Henry and Sarah moved back to Kent with the children or Sarah went alone to seek help from family I do not know. But when my great-grandfather Alfred William was born on June 8, 1863 they were back in London and living at 15 Grove Street, Poplar. James the last son was born August 5, 1865 at 2 Cottage Street, Poplar.

The family had moved six times in eleven years. I thought my nomadic life was exceptional, with twenty-five moves in forty years, but perhaps it is a family trait. It was the sixth move which would be the most devastating.

Photo: Poplar Workhouse in East London where my great-grandfather lived from the age of three to seven.

When Henry died of typhoid in 1866, at the age of 36 or 39, the latter being the age recorded on the death certificate, the six children - the youngest James, just nine months old - were put into the Poplar Workhouse by their mother. My great-grandfather Alfred was three years old. One hopes that Sarah Ann, who was twelve and Henry William, who was ten, helped comfort and care for the younger children.

The poorhouse was the only hope for survival when people reached the bottom – it was the poorhouse or the gutter. Often entire families would be admitted, or, as seems to be the case with Sarah, sometimes the children were placed so that the remaining parent, for it usually was a remaining parent, could continue to work and save the money to support them. No doubt, as she said goodbye to her children, Sarah told them; ‘It won’t be for long.’ But it was for long, a lifetime to a child – four years and only four of the six would survive them.

Life was grim in the workhouse but perhaps they took better care of the children who were admitted on their own. Even when families entered the workhouse, parents were separated from their children and men and women also lived in different quarters. The workhouse was not meant to be a place of comfort but merely a place of survival for those who had no choice. The Victorian view was that if it was too comfortable the poor would be crowding at the door to get in.

As it was, they were, but that was from desperation and need, not for a better life. Little wonder that so many set sail for the colonies.

Photo Top: The sick ward at Poplar Workhouse where my great-grandfather’s sister and small brother died of tuberculosis and Photo Below - children in the Workhouse.

But as the photographs show, the children look to be well cared for – at least physically. Given the unsanitary conditions of the areas where the poor lived in London and the malnutrition they suffered, the children in the workhouse may well have had a better chance of life. Young James and Eliza may have died of tuberculosis anyway, even if their father had lived and the family had remained together.

However, the trauma of their father dying and of being separated from their mother, whom they would only be able to see once a week on Sundays, must have wrought enormous psychological damage on the Belchamber children. In 1870 Sarah removed the remaining four children and took them home with her. Little James had died of tuberculosis aged four and Alfred’s older sister, Eliza had died at the age of eleven of the same disease although on her death certificate it states, pthisis which is the Greek term for consumption or tuberculosis.

It was six years before my great-great-grandmother married again but perhaps she had already met her husband to be and had enough support to care for them. Or perhaps after losing two she felt there was no choice.

When I first learned this history of my great-grandfather I was in tears. Having had children and now with grand-children of similar ages it upset me enormously. I have always had a great sensitivity to the suffering of children and had thought it was because of my own difficult childhood. But perhaps it goes further back than that and remains with me as a cellular memory of the terrible suffering a child would experience losing parents and home in this way. I wonder if this is what makes us who we are even more so, in that the ‘wounds’ of the past remain with us and trigger our responses accordingly.

My grandfather, John Henry ‘Jack’ Belchamber was the sixth of twelve children born to Alfred Bellchambers and Mary Ann Hambrook. They had married in 1883 and their first child was born in 1884. Of the twelve only five survived to adulthood and only four to mature adulthood. Three had died as babies, two at the age of one, one aged four and another aged five. Syphilis, which was so tragically common at the time, may well have been the cause of this mix of survival and death.

This disease had been rife in England and Europe since the 16th century and it was not until the late 1920’s that any effective treatment was found. People often did not know they had syphilis and even if they did, had no understanding of the nature of the disease and its capacity and tendency to become active and inactive at different times. During an active period, any children born would be infected, although they could appear perfectly normal – but dying either within days, weeks, months or a few years; many would also be born blind. During an inactive, or dormant period children would be born without being infected by the disease and, with all other things considered, in good health. This is why people could have twelve or more children with three or four healthy; three or four dying young and another three or four or more healthy. Or the other way around – a series of deaths followed by survival, and then another series of deaths.

There is no doubt that Syphilis was a major factor in the deaths of babies and young children in the 19th century but so too were the effects of malnutrition and poor sanitation. Malnourishment contributed to pelvic deformities in women, as did rickets and subsequent death of babies and often mothers during childbirth. Poor sanitation led to compromised immune systems and epidemics of diseases like typhoid and cholera.

Death was a part of life for my grandfather. He was born into a family where more children had died than had lived. Mary Ann born at 25 Northumberland Street, Poplar in 1886 had died before her first birthday; Henry Thomas born at 9 Flint Street, Poplar in 1887 had died at the age of four; Edith Susannah born at 15 Northumberland Street, Poplar had died aged one and Sarah Maria born 84 Tetley Street, Poplar in 1890 had died aged 18 months. By the time John Henry arrived on June 20, 1893 his parents must have learned that life was both painful and unpredictable. By this time the family had moved to 71 Gill Street, Limehouse, Poplar where they now remained for some years.

The family had moved six times in seven years which was even more ‘nomadic’ than Alfred’s parents who had moved six times in eleven years, but the consolation for my grandfather was that he did not end up in the poorhouse. Young ‘Jack’ had some certainty in that his family home remained a constant for the first eighteen years of his life, before he emigrated to Australia as part of the Boy Scouts 1913-14 farm apprenticeship scheme which had been instituted following a visit to South Australia by Chief Scout, Robert Baden-Powell, in 1912.

The scheme was advertised in the Scout newsletter and Scout column of the People newspaper in march and April 1913. John Henry William Belchamber is listed amongst the thirty-four scouts who arrived on board the SS Beltana and who formed one of the first scout troops in SA. Their story is told in Beginnings: The Story of the Beltana Boys (2008) by Anthony Aldous and Richard Mansfield.

He was nineteen when he arrived in Australia, on June 23, 1913 after lodging his application to work as a general labourer two months earlier. His first posting was to Wandearah East, via Crystal Brook, and not far from Port Pirie where some of our Camplins ended up, where he worked as a farm labourer for S.S. Searle for ten months before joining the Army in the First World War. Again, in that synchronistic way of things, I and my family would move to Port Pirie to live just 18 months after his death and Crystal Brook and Wandearah East would be places I would come to know well. I do remember until his death in 1972, that every year he would go up to the Crystal Brook Agricultural Show but until starting this research I did not know why. Neither was I interested, as one is not, in grandparents in our youth.

The address on his application for place of residence was 2 Phoebe Court, Poplar, London and this is repeated on his war records as the address of his mother, Mary Ann Belchamber.

Given the almost constant presence of death at home, it is not surprising that Jack took the chance of a better life when he had the chance. He was two years old when his five year old sister Eleanor died; eleven when his baby brother Philip died; twelve when his baby brother James died and twenty-five when his twenty-one year old brother William, died in action in the First World War.

‘Jack’ Henry also fought in the Great War, in the 43rd AIF. He joined at the age of twenty-two as a member of the battalion which was South Australia’s contribution to the Australian 3rd Division. A severe drought had hit South Australia in 1914 and during the following eighteen months the ‘farm labourer’ scheme began to fail as farmers put off their workers. The First World War had also begun and many went on to enlist, perhaps because they had little other choice.

Along with the 41st, 42nd, and 44th Battalions, plus support troops, it formed the 11th Brigade. The battalion set sail in June 1916 and after landing briefly in Egypt, went on to England for further training. No doubt Jack spent time with his family …. his first visit since leaving five years earlier. Little did he know it but he would be back for nearly a year, but in and out of hospital being treated for wounds and when he left, it would be more than forty years before he returned to England.

The battalion arrived at the Western Front in late December of the same year. Jack Belchamber, along with his fellow soldiers would spend most of 1917 bogged down in bloody trench warfare in Flanders. Unlike so many, including his young brother, he would survive. As would my paternal grandfather, Charles Vangelios Ross. In a war when so many lost sons, and often more than one son in a family, both of my grandparents fought and survived. Synchronistically, both were sent home after being injured – in the arm. My father and two uncles, as well as my father-in-law fought in the Second World War and all survived. Perhaps one other aspect of both sides of my family is more than just a little bit of luck!

Photo: John Henry ‘Jack’ Belchamber in his Australian Infantry Force uniform in 1916.

In June of 1917 the battalion took part in the battle of Messines and in October, the Third Battle of Ypres. In 1986 I went with my husband and children to live in Antwerp, Belgium for a few years, knowing nothing of my grandfather’s military past. I don’t think my mother did either because she never mentioned a connection. My paternal grandfather, Charles Vangelios Ross also fought in Belgium but recorded this experience by giving his eldest daughter, Jessie the middle name of Belgian.

I am struck by the fact that given the countless lives lost in the fields of Flanders that I should have both grandfathers fight there and survive.

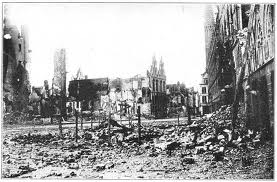

Photo: Jack Belchamber fought and lived through the devastation of the Somme.

My grandfather, like so many men in both the First and Second World Wars, never talked about his experiences. I remember visiting Ypres and sitting in a ‘museum’ set up in the back of a tavern on one of the old trench sites and looking at photographs taken during the war.

It was odd to see the desolate, cratered landscape of mud strewn with dead horses and body parts; the occasional tree stripped to a skeleton with shreds of flesh hanging from its branches and then to look up and out of the window, onto a peaceful, undulating green. That suck of blood and mud was something both of my grandfathers experienced.

Jack Belchamber, not only fought in these hellish death-holes of mud and blood, but he walked the streets of the same shattered towns and villages, which I, years later, would view as images during an afternoon visit to Ypres. So often I could see in the old photographs, the skeletal shapes of women and children searching for food. Those photographs were a reminder that always in war there are women and children, suffering, surviving and dying. The images on glass which I loaded one by one into the viewer had captured a horror which was a part of my history. Although, at the time, I did not know enough of my family ancestry to appreciate the fact.

Photo: Both of my grandfathers fought in the trenches during World War One.

He left Australia June 9, 1916 and was wounded just over a year later and admitted to the Rouen field hospital on August 2, 1917. He suffered a gunshot wound to his left arm and another to his left thigh. His upper arm bone had been fractured and reports state his thigh injury was severe.

But given the injuries of the times, these were minor. He would have gone to a dressing station and then been taken by field ambulance to a casualty clearing station before being transferred to a base hospital, in this case, Rouen.

Front-line units, such as infantry battalions, were able to provide only the most superficial medical care. Located near the front line, often in a support or reserve trench, would be a Regimental Aid Post, attended by the Battalion Medical Officer and his orderlies and stretcher bearers. A wounded man would either make his own way there if possible, or be carried. I am guessing Jack was carried if his thigh injury was severe. The facilities were crude and often a wounded man would get not much more than a drink and a few words of comfort before being handed down the chain to the Advanced Dressing Station. Hand carriages, wheeled stretchers and trolley lines were used to move the wounded. Those who could walk did. From 1916, relay posts for stretcher bearers were established every 1000 yards or so. To avoid congestion, certain communication trenches were allocated for the removal of casualties. By the time my grandfather was injured the system was giving much better survival odds for the wounded.

He was shipped out to England on August 28, admitted temporarily to Exeter hospital and later being transferred to Harefield, Weymouth and then London as his treatment progressed. It would be six months before he was well enough to be shipped home to Australia. He was discharged in Melbourne at Victoria Barracks, on May 28, having arrived back on May 10 on the Orontes.

He had served for two years 123 days and his service abroad had been for one year and 326 days… he was twenty-four years old..

Synchronistically, my paternal grandfather, Charles Ross was also wounded in the left arm during the First World War and discharged early as medically unfit. He had been wounded in 1915 in the Dardanelles and he had been discharged and sent home after being treated in Malta. I can only wonder if the two of them had more to talk about than they expected when they met in 1946 for the marriage of their children. They may have known each other already given that the Ross’s lived around the corner from the Belchambers, in Leicester Street, Parkside and my parents had met as children, seeing each other at school and in the street.

In those months after his return I like to think that while he did not have family, he had the support of friends. One assumes he felt relief at being safely home. No doubt there was pain as his injuries slowly healed. But was there physiological pain as well? The First World War trenches had been the scene of some of the bloodiest and most horrific fighting that soldiers had ever known.

Photo: The town of Ypres was destroyed by German bombing. Women and children scavenged in the ruins in order to survive.

Did he wake in the middle of the night in fear, the smell of blood and flesh and mud in his nostrils? Or was he the sort of man who took such things in his stride; buried it deep so it could not hurt? My mother said he was a hard man in many ways. She did not remember him being affectionate. But she did not remember her mother being affectionate either. Then again, my mother was not affectionate with me although she was with my younger brothers and sister when they were small.

Photo: Jack Belchamber arrived back in Australia on the Orontes in May 1918.

The guns would not fall silent until November 11 and most soldiers in the 43rd battalion would not be demobbed until 1919. By the time the Treaty of Versailles was signed on June 8, 1919, Jack was back at work and living as normal a life as one can after such an experience. Two years later he married Hilda. If he was like my father he would never have talked to his wife or family about the war.

My father was only seventeen when he went to war – he lied about his age – and fought in the jungles of the Philippines. The experience haunted him and turned him, in the main, into an angry man – an anger no doubt sourced in what would now be called post-traumatic-stress disorder and resulting depression. Anger and depression can be found in both sides of my family and depression has been linked to repressed rage.

There is a commonality to the human experience in that all of us have had ancestors who lived with fear; the difference I suspect is in the ability to handle fear. For some, like my great-grandmother, it is expressed outwardly as rage and for others, like my mother and her mother, it is expressed inwardly as depression.

Photo: Celebrating the end of the First World War in the city of Adelaide, south Australia. Jack Belchamber was probably amongst the crowd.

Jack Belchamber was much older than my father when he went to war but perhaps he was damaged all the same; how could one not be given the sheer level of horror which was trench warfare in Flanders. He did not become an angry man, but he was, according to my mother, a man closed off to feelings. This was not the man of whom my great-aunt Maude spoke when I met her in England in the early seventies and then again in the mid-eighties …. the Jack she knew was a light-hearted young man; but that was the Jack who had not been to war and the Jack who returned for a three month visit nearly half a century after the war had ended.

Then again, his sober, serious, sensible side had no doubt been revealed when he joined the Boy Scouts. Or perhaps it was pragmatism – joining an organisation which offered some hope of advancement for an intelligent, but poor boy with limited opportunities for education.

The man my mother knew as father was a serious, severe man who joined the Independent Order of Rechabites, a benefit league for teetotallers originally founded in England in 1835. But the man his sister and family knew, staggered down the gangplank on his return visit to England in the late 1950’s. His teetotalling days had ended on the six week journey from Adelaide to London. We had all gone down to Port Adelaide to see him off on the ship; sent him home sober to his family and they were greeted by a drunk. Somehow I like to think that he was happier when he could once again have a drink. I remembered my grandfather as a man who liked a glass or three of port but I never saw him drunk! Perhaps it took six weeks of boredom and freedom to achieve that.

We are formed by our experiences and there is no doubt that the man my grandfather was and as a result, the woman his daughter was, and who I am in turn, is linked back through the years to the experiences of our ancestors. My mother had a shandy – beer and lemonade- occasionally in the early years of marriage but for most of the time I knew her, was a teetotaller as her father had been for much of his life. She disapproved of my father drinking, which he did, often heavily, to such a degree that he kept his sherry in the shed and drank alone, as and when he could.

I don’t remember my grandfather as a warm man; in fact I think I was frightened of him. He was not so much cold as distant but then he had been born to a father who had lost his father and his mother at the age of three and who had spent the four most formative of his years in the horror of the workhouse. And he had been born into a family which lived cheek by jowl with death. Not only that, but he had survived the horrors of the Somme and the Belgian trenches. Why would he risk feeling very much at all?

I don’t remember my mother talking much about her father, nor grieving terribly when he died. It was the death of her mother which haunted her. Hilda, she of the dark, sorrowful eyes who according to my mother spent most of her life in a state of depression …. as did my mother.

While there are no doubt genetic inheritances which help to make us who we are, I also believe there is something called ‘cellular memory’ and that is passed down through the generations as well. The feelings and experiences and memories of our ancestors make up this cellular memory.

My mother had generations of the most terrible poverty on the English side of her family as we know and probably similar levels of poverty on the German-Danish side. The Hasch-Kohlhagens did not emigrate for reasons of religious persecution so it must have been in the hope of a better life.

There is also evidence in the maternal line of emotional/psychological challenges. My mother suffered from crippling depression and anxiety for most of her life; her sister, Joyce Marina, eleven years her junior, also experienced a number of nervous breakdowns. Hilda Gertrude suffered from depression according to my mother and was often barely functional. My great-grandmother Sarah Ann had a terrifying temper, and given that depression is often sourced in suppressed rage it is reasonable to assume that all of them experienced disturbing amounts of frustration and rage, but merely ‘expressed’ it differently. My great-great-grandmother, Eliza Ann took an overdose of opium at the age of sixty-seven which is unlikely to be the act of someone who has led an emotionally and psychologically tranquil life.

Photo: Hilda Gertrude Hasch(right) and her sister Lillian circa. 1915. The sadness in Hilda's eyes remains a constant.

I have had my own ‘battles’ with darkness although nothing like my mother or those who came before her. But then I was born into a different world, where psychological problems were not seen as shameful and where women, while still repressed, were not brutally subjugated in the way that they had been.

There is a sensitivity here and perhaps, in a world where women were not so subjugated and suppressed, my mother, grandmother, great-grandmother and great-great grandmother and beyond might have been seers, healers and magicians. Psychic energy denied turns into madness.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete